Iceland may be the last exposed remnant of a nearly Texas-size continent called Icelandia that sank beneath the North Atlantic Ocean about 10 million years ago, according to a new theory proposed by an international team of geophysicists and geologists.

The theory goes against long-standing ideas about the formation of Iceland and the North Atlantic, but the researchers say the theory explains both the geological features of the ocean floor and why Earth's crust beneath Iceland is so much thicker than it should be. Outside experts not affiliated with the research told Live Science they are skeptical that Icelandia exists based on the evidence collected so far.

Even so, if geological studies prove the theory, the radical new idea of a sunken continent could have implications for the ownership of any fuels found beneath the seafloor, which under international law belong to a country that can show their continental crust extends that far.

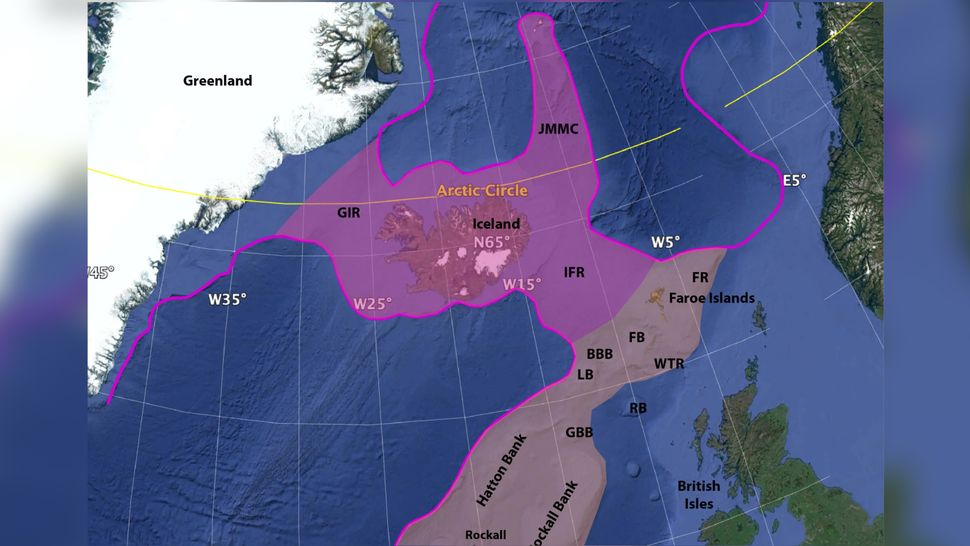

The region that's got continental material underneath, it stretched from Greenland to Scandinavia, said Gillian Foulger, lead author of Icelandia, a chapter in the new book In the Footsteps of Warren B. Hamilton: New Ideas in Earth Science (Geological Society of America, 2021) that describes the new theory. Some of it in the west and east has now sunk below the surface of the water, but it's still standing higher than it should. … If the sea level dropped 600 meters [2,000 feet], then we would see a lot more land above the surface of the ocean, Foulger, an emeritus professor of geophysics at Durham University in the United Kingdom.

The North Atlantic region was once entirely dry land that made up the supercontinent of Pangaea from about 335 million to 175 million years ago, Foulger said. Geologists have long thought that the basin of the North Atlantic Ocean formed as Pangaea began to break up 200 million years ago and that Iceland formed about 60 million years ago above a volcanic plume near the center of the ocean.

But Foulger and her co-authors suggest a different theory: that oceans began to form roughly south and north but not west and east of Iceland as Pangaea broke up. Instead, the geologists wrote, the areas to the west and east remained connected to what is now Greenland and Scandinavia.

Foulger said, people have this highly simplistic idea that a tectonic plate is a kind of like a dinner plate: It just splits in two and moves apart. But it's more like a pizza, or a piece of artwork made from different materials some fabric here and some ceramic there so that different parts have different strengths.

According to the new theory, Pangaea didn't split apart cleanly, and the lost continent of Icelandia remained as an unbroken strip of dry land at least 200 miles (300 kilometers) wide that stayed above the waves until about 10 million years ago, Foulger said. Eventually, the eastern and western ends of Icelandia also sank, and only Iceland remained.

The theory would explain why the crustal rocks underneath modern Iceland are about 25 miles (40 km) thick instead of about 5 miles (8 km) thick, which would be expected if Iceland had formed over a volcanic plume, the geologists said.

Foulger said, when we considered the possibility that this thick crust is continental, our data suddenly all made sense. This led us immediately to realize that the continental region was much bigger than Iceland itself there is a hidden continent right there under the sea.

Foulger and her colleagues estimated that Icelandia once stretched over more than 230,000 square miles (600,000 square kilometers) of dry land between Greenland and Scandinavia an area a bit smaller than Texas. (Today, Iceland measures about 40,000 square miles or 103,000 square km.)

They suggested that there was also a similarly sized adjoining region, making up "Greater Icelandia," to the west of what is now Britain and Ireland. But that region, too, has sunk beneath the waves, they said.

Fossil evidence showed that some plants that spread by dropping seeds are identical in both Greenland and Scandinavia. That finding reinforces the idea that a wide strip of dry land once connected the two regions, the authors said. However, the geologists are not aware of any fossil evidence of animals on the lost continent.

Geographer Philip Steinberg, director of Durham University's Centre for Borders Research, said the new theory of Icelandia could have implications for the ownership of fossil fuels beneath the seafloor; under international law, countries can claim those fossil fuels if the evidence proves the resources reside beneath that country's continental shelf, a relatively shallow region of the seafloor that can extend hundreds of miles beyond the coast.

Steinberg, who was not involved in the Icelandia research, noted that countries around the world are spending large amounts of money on geological research that could allow them to claim exclusive mineral rights beneath their continental shelves.

Steinberg said, research like Professor Foulger's, which forces us to rethink the relationship between the seabed and continental geology, can have a far-reaching impact for countries trying to determine what area of the seabed are their exclusive preserve.

The concept of Icelandia goes against prevailing theories for the formation of the North Atlantic region, and several prominent geologists and geophysicists are critical of the idea. Ian Dalziel, a geologist at the University of Texas of Austin, who last month won the Penrose Medal for his work on ancient geography and past supercontinents, said he could see little to justify the proposal.

Dalziel said, unlike the sunken continent of Zealandia, for instance, which geologists have established was composed of continental crust that separated from Antarctica and then sank, there was not enough continental crust material in the North Atlantic region to have formed Icelandia.

Geophysicists Carmen Gaina, director of the Centre for Earth Evolution and Dynamics in Oslo, and Alexander Minakov of the University of Oslo said, the proposal was a bold claim that had several problems, and that the existence of Icelandia was unlikely.

For instance, magnetic surveys of the seafloor in the region show stripes that indicate when successive layers of molten crust were laid down on the seafloor of the North Atlantic as the Earth's magnetic field changed polarity over millions of years a clear sign of oceanic crust also seen in large oceanic plateaus in the Pacific Ocean.

Gaina and Minakov said, but their conceptual view is a good starting point for discussions and more importantly, for more and relevant data collection. Such as further geological drilling on the seafloor and seismic surveys that can measure the crust from its seismic echoes of calibrated explosions carried out by research ships.

0 Comments